When visiting the US Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C., an “Orientation theater” is the first stop for visitors. In a brief 13 minutes and in Hollywood style, we are introduced to its history and some of its most distinctive features. Although enlightening and educational, it is no easy task to encapsulate such a rich history in so short a time. It is equally difficult to succinctly portray the characteristics of the American Congress in a few lines – the goal I have set myself.

Article I of the United States of America places Congress at the center of American governance, giving it primary responsibility for lawmaking and conceiving it as the most representative branch of the federal government. For these reasons, the literature has focused extensively on this institution. I will therefore leave some suggested reading at the end of this text.

The US Congress has a bicameral structure, made up of two legislative chambers, the Senate and the House of Representatives, which meet separately in the two wings of the Capitol. Each chamber operates under its own rules and procedures and in different environments, and has its own leadership. The choice of a bicameral structure, to the detriment of a unicameral structure (as in the case of Portugal and most other countries¹), like other institutional choices, is grounded in history. In The U.S. Congress: A Very Short Introduction (2010:), Donald A. Ritchie tells the story (very possibly false, according to the author) that Thomas Jefferson questioned George Washington about the need for a Senate in the configuration of the American government. Washington is said to have asked: “Why do you pour your coffee into the cup?” “To cool it down,” Jefferson replied. “That’s exactly why we created the Senate,” said Washington, “to cool it down.”

Whether true or false, this story clearly reflects the importance of the system of checks and balances² in the American political system; whether through the division of federal powers between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, or through the bicameral structure chosen for the legislative branch. The importance of this system of balances is clearly evident in the “Federalist papers” written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison. These help us to understand the institutional design drawn up in the 18th century, although the textual expression “checks and balances” is curiously not part of the American Constitution.

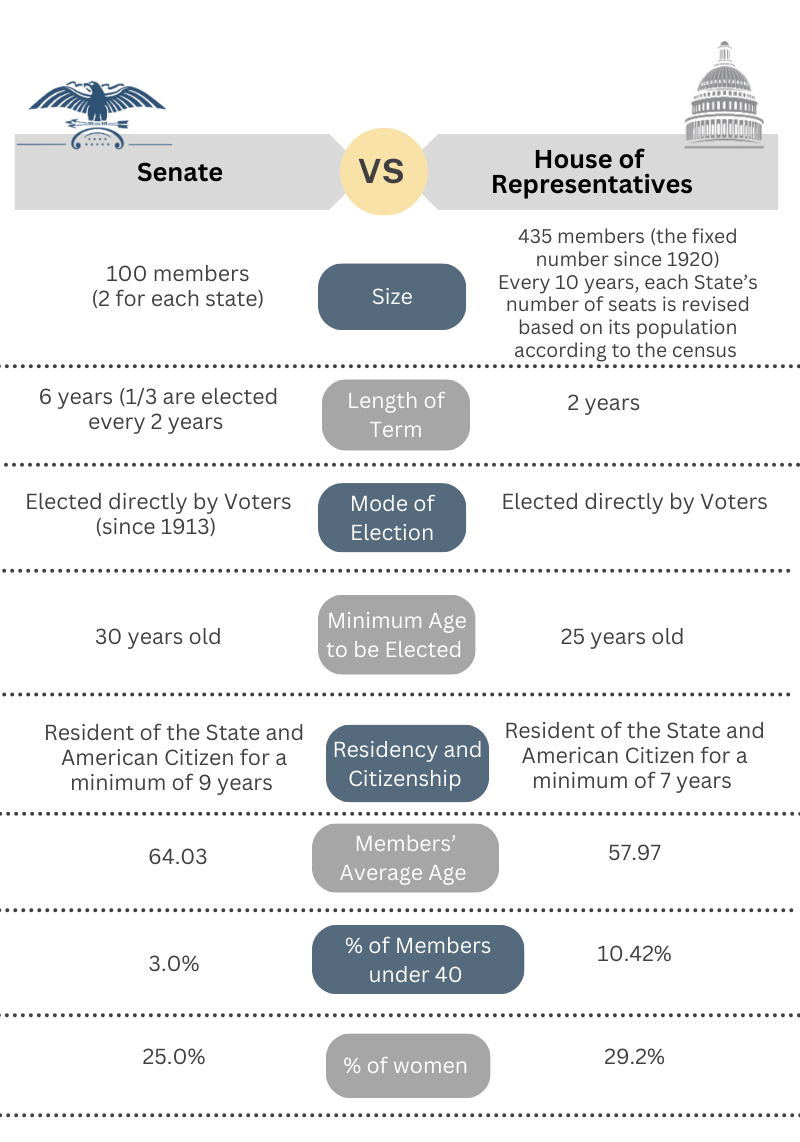

The Senate (upper house) is thus seen as a second branch of the legislative assembly, distinct from the House of Representatives (lower house), but sharing power with it. Both bodies are also responsible for scrutinizing the executive. The House of Representatives is elected every two years, thus guaranteeing the necessary and desired responsiveness and accountability to the electorate³. On the other hand, and according to the “Federalists papers”, the Senate was designed to give the government sufficient credibility with international powers, a body that would hold office for a longer period, providing the necessary continuity for diplomatic commitment to the international order. But how do these two chambers differ? Do they have the same powers? And what is the social fabric that makes them up?

The two chambers have largely identical legislative powers. It is therefore a case of ‘perfect bicameralism’, which is more common in presidential and federal systems (as in Switzerland, with the Federal Assembly Ständerat). In parliamentary systems, the chambers usually have relatively asymmetrical powers (as is the illustrious case in the United Kingdom). They thus share many competences, such as regulating immigration and naturalization policies or the ability to declare war, among others⁴. Despite this symmetry, there are some important exceptions: for example, the House of Representatives has the exclusive power to initiate bills that involve changes in tax revenue or to initiate impeachment proceedings. In turn, the Senate has the exclusive power to judge the impeached official and decide on their possible removal from office. This division between the “power to initiate and accuse” and the “power to judge and potentially remove” is again representative of the system of “checks and balances” central to the American political system. As a matter of interest, since the first impeachment in 1797, the House of Representatives has initiated this procedure more than 60 times⁵.

Let’s now look at some of the particularities that make up the two US Congress chambers, illustrated in the following table.

The US Congress in numbers:

Sources: Data taken from the US Constitution and the “PARLINE” database of the Inter-Parliamentary Union

A total of 468 seats in the U.S. Congress (33 seats in the Senate and all 435 seats in the House) will be disputed in this year’s elections, on November 5. The results could again change the power dynamics in Washington in the coming years.

The new Congress will face many complex party-political, geopolitical, economic, and social challenges, both at home and abroad. I would highlight one particular challenge, which is perhaps less prominent: the relationship between this institution, considered by many to be the “central pillar of the constitutional system” (Mann & Ornstein, 2006:242), and US citizens. Data from September of last year indicates that only 26% of US adults have a favorable view of Congress⁶. This leaves a question and concern: How can Congress contribute to improving its image and strengthening its relationship with public opinion in the particularly challenging and polarized context that the US (and the world) is experiencing?

My reading suggestions:

¹According to data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union, 112 countries have a unicameral structure and 78 a bicameral structure.

²The term ‘checks and balances’ does not appear verbatim in the Constitution itself, but it is used in the “Federalist papers”.

³Ideas present in papers 62 and 63.

⁴US Constitution, Article I, Section 8.

⁵https://www.loc.gov/nls/new-materials/book-lists/the-history-of-impeachment/.

⁶Data available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/09/19/evaluations-of-members-of-congress-and-the-biggest-problem-with-elected-officials-today/.

Related Posts

March 25, 2025

Note of Condolence – Charles Buchanan (1934-2025)

June 3, 2024